Desde que pisé Japón me encuentro constantemente con cosas muy extrañas… La gran gran mayoría interesantes y divertidas de ver; pero luego hay veces que me topo con cosas mucho más extrañas (y que tal vez de lo simples que son, ¡más extrañas me parecen!) a las que, verdaderamente, no les encuentro explicación…

Since I stepped in Japan for the first time, I’ve found many things or customs that I had never seen before in my life… However, I have also found myself in situations where I couldn’t find an explanation at all!

Y me encantaría que alguien fuera capaz de explicármelo. Así que, si alguien encuentra alguna buena respuesta, ¡que la comparta conmigo! Aquí las tenéis… ¡Mis primeras 10 PREGUNTAS SIN RESPUESTA sobre la vida en Japón!

And if anyone ever finds a good answer to them… Please, feel free to share them with me! 🙂 This is why here you are my first 10 QUESTIONS WITH NO ANSWER about the daily life in Japan!

1. ¿Por qué hay un par de zapatillas en cada toilet (WC) si van siempre descalzos por la casa? Why are there slippers in the toilet room if they are always barefoot at home?

En serio, si vas en calcetines por toda la casa… ¿Por qué te pones zapatillas de pronto para hacer pipí? ¿Para tener que perder más tiempo en colocártelas en vez de ir directamente hacia el váter? Y, además, en cuanto a tener los pies «protegidos», ¡en los cuartos de baño de algunas casas también hay alfombra!

Seriously, if you only wear socks at home, why would you suddenly use slippers just to pee? Why would you waste time on that instead of directly heading to the toilet? What’s more, if they do it for keeping your feet warm or ‘protected’, there’s still no sense! Cuz then how would homes with carpet justify it?

Según lo que he oído, es para evitar tocar el suelo, ya que, al ser «la habitación del pipí», éste podría estar más sucio. Pero sinceramente no le veo el sentido, porque en tu propia casa el suelo del baño no suele (ni debería) estar sucio como sí ocurre en los bares… En todo caso tendría sentido para los invitados, para que no les dé cosa entrar descalzos en un toilet room que no sea el suyo. Pero vaya, que si no hay confianza, ¡te aseguro que no estaría ese invitado en esa casa! Además, si hay algo que tratan de mantener limpio al cien por cien, como ya comenté describiendo la limpieza de Año Nuevo, es el suelo.

According to what I’ve heard, they do it so that they don’t touch the floor, just in case it’s not hygenic. However, I can’t understand yet, as the toilet at home doesn’t get as dirty as public toilets. I might understand the case of having guests, as they could be kind of reluctant for not being their own toilet. But STILL: there’s nothing as clean as a Japanese floor! That’s what they make sure they clean as much as possible as I described in the New Year’s cleaning ‘party’ (obviously not a party)!

Lo que sí tiene sentido es lo que pasa en los restaurantes, donde también te encuentras las zapatillas en el suelo. Pero este es sólo el caso en el que te tienes que descalzar para comer/cenar en ese restaurante (sí, los hay, y son muchos). Entonces, cuando quieres ir al baño, como es un baño mucho más frecuentado y a saber cómo te lo vas a encontrar (que aun así suele ser limpio, esto es Japón), te colocas esas zapatillas de plástico súper horteras y, hala. Objetivo cumplido. ¡Aquí sí lo entiendo! ¿Pero en tu propia casa? ¡Me paso los días tropezándome con las zapatillas nada más entrar!

The only place where I can understand people use those ugly plastic shoes at the toilet is at restaurants. But just in restaurants where you have to take off your shoes when you enter the establishment. That’s something typical in traditional restaurants. You’ll probably find them when you travel to Japan! So here I can understand, as many people would enter there and you can’t perfectly control how clean it’ll be. But do not have those shoes in houses, please, cuz I keep on bumping into them! (Gaijin perspective)

2. ¿Cómo se lavan todos los rincones de su cuerpo en los onsen? How do they wash all their body at onsen?

Vale, antes que nada expliquemos qué son los onsen:

First things first. What’s an onsen?

Los sento u onsen, para los que no lo sepan, son unos baños termales donde los japoneses suelen ir de vez en cuando para bañarse allí. Es como un spa, pero solo de agua caliente y donde hay que ir desnudo. Sí, desnudo (comprended entonces que no tenga fotos para ilustraros). Este requisito es lo que le echa para atrás a la mayoría de extranjeros, normalmente hombres, a la hora de vivir la experiencia de ir al onsen. Pero os aseguro de que es muy recomendable.

Sento or onsen are, for those who don’t know yet, are public baths where Japanese people often go to take a bath and relax. They take a bath (and a shower) every day, but between once a month and half a year they also attend these places alone or with friends to have a really hot bath (like in a spa) and relax… Naked. Yes, absolutely naked, no swimmers -so forgive me I don’t include a photo this time. That’s not relaxing for some foreigners, I know. You’d be naked depending on the circumstances but not in front of unknown people. Well, Japanese do. And it’s true it’s relaxing. Just give it a try when you visit Japan!

Pues bien, como ahí te bañas sin bikini ni bañador, lo más higiénico (se supone que todos lo hacen) es ducharse nada más entrar en el onsen (sí, en una especie de duchas comunitarias donde todos te ven «pero nadie te mira...») para meterse en el agua ya limpitos y mantener así la pulcritud.

As you must be completely naked when entering the baths, in order to keep the hygiene in the place, the logical thing is to take a shower as soon as you get in there, so that you enter the pools once you’re fully washed and clean. Everyone is supposed to do it and you’ll find a line of showers with a stool each to sit on it.

Entonces te diriges a las duchas y, lo primero de todo, te sientas en un banquito. Así, sentado/a es como te lavas todo: el cuerpo y el pelo. Y AQUÍ es donde viene mi pregunta…

So, as I said, you just head to the shower, you sit down on the stool and there you wash all your body. And HERE is where you’ll come up with the same question as me (I guess):

Si se duchan sentados en un banquito y luego no se levantan un poquito siquiera para enjabonarse la zona en contacto con el banquito (la zona crítica, por cierto), ¿cómo se la lavan?

If they take a shower seated on a stool and they don’t stand up even a bit for keeping washing their piece of body touching the stool (important one btw)… How do they wash it?

He de decir que no voy al onsen a diario, obviamente. Así que no he podido comprobarlo muchas veces, pero sí unas seis aproximadamente. Y aun así debería ir algunas veces más para intentar encontrar la respuesta (o descartar esta pregunta). Porque si se levantan para lavarse bien, ¡os digo yo que son tan discretos que no me entero!

I must say I don’t go to onsen every day, obviously, so I haven’t done enough research (around 6 times). If they really do stand up to wash themselves… they’re too discreet I can’t notice! And of course I’m not staring at them. That’s an important unspoken rule at onsen which makes me actually feel comfortable there. Otherwise, no one would, I guess.

Y es más (aquí experiencia personal), la tercera vez que fui a uno tenía una señora mayor sentada al lado mía duchándose. Y cuando empecé a lavarme me miró de pronto (de ahí lo de «nadie te mira«, porque no me han mirado nunca fijamente excepto en esta ocasión) y pensé: «A ver, tendré que lavarme bien si quiero compartir una bañera gigante con otra gente, ¿no? ¿Qué le estará sorprendiendo?»

What’s more (here is a personal experience), the third time I went to a sento I was having a shower next to an old woman. When I started washing myself there she suddenly looked at me (she broke my unspoken rule!). I wondered why she’d be surprised!

Ok, too much truth in this post.

3. ¿Cómo pueden las personas mayores (y especialmente las que tengan una bajísima movilidad o aguante muscular) hacer sus necesidades en los váteres japoneses tradicionales? How do old people (and especially those with low mobility or strength) use their traditional toilet?

Bueno, perdonad que esto esté tomando una perspectiva tan… ¿»íntima»? Aunque yo preferiría decir, higiénica, ya que es la temática de las 3 preguntas que llevo por ahora. Pero entendedme también. Suelen ser los momentos en los que voy sola y no puedo preguntar. Y si pregunto después (tal vez pregunte demasiado), intentan ignorar mi pregunta descaradamente porque se trata de algo «demasiado personal». Pero vamos, que personal no es, porque es común para todo el mundo, ¿no?

Well, I’m truly sorry this is taking this… private? direction. Or hygienic, I’d say. That’s the theme of these last three posts, yeah. But understand me. Whenever you are alone you have no one to ask this to (and I’m a curious person), and when I’m with Japanese friends, they’ll most of the time smartly ignore my question and change topic. Guys, these are questions every human in the world share!

A lo que iba: Los váteres tradicionales japoneses son, para que nos entendamos, «agujeros en el suelo«.

So heading back to the topic: Traditional Japanese toilets are, for you to understand me, ‘a hole in the floor’. Same as toilets in non-developing countries, that’s right. Japanese contradictions.

En serio, si nunca habéis tenido la oportunidad de probar un váter así, os describo la experiencia: doblar las piernas hasta agacharte completamente, hacer equilibrio… (hasta aquí normal para todas las chicas que necesitamos un baño donde no lo hay). Pero si estar un rato aguantando así el equilibro ya es un deporte extremo para mí… ¡Mi abuela directamente se caería y se quedaría tirada en el suelo (Dios quiera que no en el «váter-agujero») de por vida!

Okay, so provided you’ve never had the chance of trying these toilets I’ll explain to you the situation: you bend your knees so you find yourself squatted, you hold on your equilibrium (women understand this so far right? Especially at deserted areas such as forests)… And imagine you need to keep this situation, for a long time. I’m not even fit enough! Imagine your grandma then. Mine would definitely fall down and stay there til someone help her stand up (let’s hope God didn’t let her fall down into the ‘hole-wc!’)

Pues eso, que siento la dirección que está tomando esta entrada del blog, pero no me quiero imaginar a nadie ahí con la barriga suelta… Ni a los abuelitos japoneses, que como ya os he dicho, al tratarse de váteres tradicionales no serán pocos los que los tengan (yo he estado en casa de una amiga donde ESE es el váter que tienen).

So yes, I apologize again for these topics but I promise you this will change right now. I hope you never get sick having these toilets. And I hope the Japanese elderly don’t have these toilets at home, ‘though I know many of them will do… Cuz I’ve stayed at one house like that.

4. ¿Por qué el pan bimbo es el doble de gordo? Why is the Japanese sliced bread much thicker?

¡Bien! ¡Cambiamos de temática! Sí, si comparas el pan de molde español (o australiano, por ejemplo) con el pan de molde japonés, verás que el de allí es el doble de gordo. ¡Y encima es caro! Pero luego cuando vas a un convini (tienda 24 h) te encuentras sándwiches hechos con pan «bimbo» normal… Sin sentido.

Yey! We changed topic! I told ya. And yes, if you compare Spanish (or Australian, for example) sliced bread with the Japanese, you’ll find theirs is doubly thicker! And more expensive! However, at convinis (7-eleven) you can find sandwiches made of our actual sliced bread. So why do they have (and prefer) the thicker one?

Eso sí, ¡para mí está más rico el de Japón! Será que como le llaman «pan» tal cual intentarán que también sepa a pan real en lugar de a pan industrial (por eso no soy fan del pan de molde español).

And yet I find more yummy the Japanese sliced bread! Maybe that’s due to the name (they called it just ‘bread’) whereas in Spain we usually emphasize it’s ‘sliced bread’ as it seems less healthier and the taste is worse than a baguette’s. That’s why I don’t really like Spanish sliced bread, as we already have good quality baguettes!

5. ¿Por qué el símbolo del yen es diferente en japonés y en el resto del mundo? Why the yen sign in Japanese is different from the rest of the world?

Vale, esto va cambiando aún más de temática, y es que ¡me parece súper raro! Nosotros escribimos ¥ y ellos escriben 円. Si euro es € en español, en inglés y en japonés, ¿por qué «yen» no se escribe solo ¥ o solo 円?

Alright, we keep on changing topic. And this is true I find it quite rare! We write ¥ while they do 円. If euro is € in Spanish, English and Japanese, why isn’t ‘yen’ written only as ¥ or円?

¡Y para los números también tienen símbolos distintos!

And the same situation can be found with numbers:

1 一 2 ニ 3 三 4 四 5 五 6 六 7 七 8 八 9 九 10 十

Imagino que esto de los números será debido a que, como los árabes estaban centrados en Europa, África y Asia occidental, Asia oriental iba a su rollo. Y tiene sentido, porque los números en chino también son esos (el idioma japonés se desarrolló en buena parte gracias al chino). Eso sí, hoy en día los japoneses también usan nuestros números, pero en restaurantes y bares muy locales aún verás los números japoneses. ¡Apréndetelos bien si quieres saber por cuánto comerás antes de pedir!

I imagine the numbers issue is based on the Chinese influence (Japanese got part of their alphabet from the Chinese language) thanks to its proximity, same as we European use the arabic numbers. Nowadays, Japanese also use the arabic ones, but you’ll still find a lot of the Chinese ones on local restaurant menus.

6. ¿Por qué lavan los envases (ya vacíos) de los yogures? Why do they wash the yogurt containers?

Mejor dicho… ¿Por qué no los lavamos en España? ¿Por qué nadie nos ha dicho que lo hagamos? Yo pensaba que en el proceso de reciclaje viene incluida una fase de lavado, y que por eso da bastante igual. Pero si es necesario, lo hago. ¡Aquí sí espero respuestas! Si alguien se ha documentado antes de que yo lo vaya a hacer (que si tengo que esperar tanto como para publicar este post, me tiraré mínimo un año más), por favor que lo cuente.

Or let’s say… Why don’t we wash them in Spain? I thought there’d be a washing step during the recycling process so it wouldn’t be relevant to wash the containers before throwing them to the rubbish. However, I’m not expert at all so if there’s anyone who have done a better research, please share!

7. ¿Por qué los japoneses no tienen frío? Why do Japanese never feel cold?

Yo siempre escucho a la gente decir por la calle «samui» («¡qué frío!»), pero… ¡Lo que veo es bien distinto! Tobillos al aire, chicas en uniforme y calcetines, hombres enchaquetados (y sin ningún abrigo extra)… ¡Y todo eso a 5ºC! ¡Cinco! ¿¿¿¿Hola???? ¿Es que tu madre nunca te ha repetido hasta la saciedad que te abrigues al salir de casa?

I always hear people in the streets saying ‘samui!’ (‘it’s cold!’) but… That’s what I hear! What I see is absolutely different! No long trousers or skirts, socks instead of tights, salary-men wearing no coat… And maybe it’s 5ºC outside! Don’t you ever hear your mother say ‘keep warm when you go out!’?

Y lo contrario con el verano, se abrigan demasiado (incluso con guantes) y aún no entiendo para qué… ¿Evitar ponerse morenos? ¿Evitar cáncer de piel (creo que esta es la que menos piensan, la verdad)? ¿No enseñar los hombros o un pelín de escote pero llegar al trabajo en un mar de sudor (sí, así se va por la calle en verano, literalmente)? ¿Hacer senderismo en verano con leggings, camiseta térmica, cuello alto, y encima el chándal de manga corta y pantalón corto? ¿Por qué no directamente el chándal? Bueno, dejamos esto para otra posible tanda de preguntas.

And summer is exactly the other way round. They even wear gloves! And I still don’t understand the reason. Is it to avoid getting tanned? Is it to avoid suffering from skin cancer (I doubt this is the most important one for them)? Not to show their shoulders or neck but instead arrive at work immersed in a sea of sweat (this is literally what Japan is in summer time)? How can they go hiking in summer wearing leggings, heattech T-shirts, long neck T-shirts and the summer sport clothes on top? Why not only one layer? Okay, let’s leave it for a second round of questions with no answer.

8. ¿Por qué son tan prácticos en unas cosas… ¿Y tan atrasados en otras? Why do they make some stuff so practical… And some other so undeveloped?

Venga, en serio. ¿Japón avanzado? Tienen los váteres más modernos del mundo (próximamente en el blog) pero… ¿Y qué pasa cuando hablamos de temas del banco? ¿Y el uso de tarjetas de crédito? ¿Y con mandar una carta?

Let’s be serious. Japan fooled me (on everyone in the world) when talking about development. It is obviously developed and they have the best toilets in the world but… What about banks? Or payments with credit cards? Or how to send a letter?

Esta temática podría dar para un post entero, pero me voy a centrar en pocas cosas (si enumerara todas las que vi, no terminaría).

We could write a whole post about this (I will!), but I’m gonna focus in just a few of them.

El inkan. Ya lo expliqué en «Cómo abrir una cuenta bancaria en Japón». No voy a explicar otra vez lo que es, tan solo voy a dejar la imagen. ¿Cómo es posible que haya que firmar TODO con un sello que además tan solo representa tu apellido y que cualquiera puede tenerlo? ¿No es mucho más útil y práctico una mera firma?

The inkan. I already explained what it is in the post ‘How to open a bank account in Japan’, but I’m gonna leave the picture below. How is it possible you need to sign everything with a personal stamp that only shows your family name and thus anyone could sign that for you? I know this can happen with our signature as well, but at least it’s way more practical.

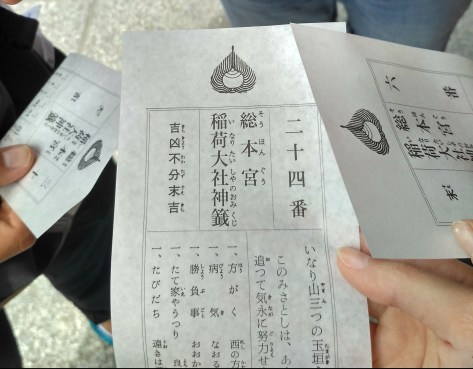

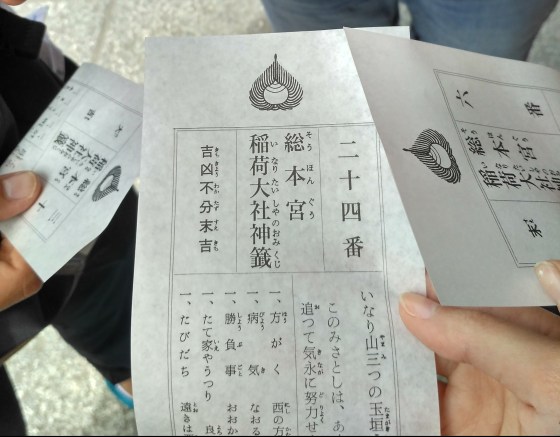

Mandar una carta. Nosotros pegamos los sellos correspondientes al país o continente al que va dirigida la carta (España, Europa, etc.) y ya está. Aquí pesan la carta (infladas con aire, encima -como podéis comprobar en la imagen-) y según el peso les asocian un precio y otro (y para pagar el precio correspondiente pegan los sellos equivalentes a ese precio). ¿No es un poco pérdida de tiempo y energía pesar cada carta para pagar un folio de más? ¡No sabéis lo chocante que me resultó tener que pesar una carta cuando tan solo era un papel que tenía que mandar a la ciudad de al lado! Si fuera un paquete lo comprendería, pero una carta… No sé, tal vez soy una exagerada.

Sending a letter. At least in Spain, we usually stick stamps to the letter according to the destination (whether it’s national or international delivery). And that’s all. But in Japan, they weight the letter (and what’s more, they’re previously inflated with air so it weights more -sorry, so it’s, more ‘kawaii’ (cute) I guess -up to you). So they set the price according to the weight and then you pay and stick the necessary stamps for completing that price. Seriously, it was pretty shocking for me. That’s why I took these photos.

9. ¿Por qué me preguntan si me he comprado aquí el chaquetón? Why do they ask me if I bought my coat here?

Volviendo un poco al tema del frío. En serio, dos o tres veces me lo preguntaron nada más ver. ¡Ni que no hiciera frío en otros países, o en España mismo! ¡También tenemos invierno!

Going back to the ‘cold’ topic. Seriously, I’ve been asked that twice or thrice by my friends in different situations right after saying hi to them. Am I the only one who may find it strange? If it wasn’t cold in other countries! Even in Spain we do have winter!

¡Y buenas tiendas! Que lo que hay fuera de Japón también son países desarrollados. Cuando comenzó el invierno, muchos me recomendaron encarecidamente el heatech (la palabra correspondiente a «térmico/a» en Japón, por lo que las camisetas térmicas aquí vienen con el sello «heattech»), ¡como si fuera la alta tecnología japonesa la que hace que sean así de calentitas! ¡Pero si yo encuentro camisetas térmicas muy buenas en un mercadillo cualquiera y no son de tecnología japonesa ni nada!

And we do have good stores! Outside of Japan it’s also developed countries. However, some people suggested me to buy some heattech t-shirts, letting me understand I didn’t bring good enough quality clothes for winter, as heattech is one of those amazing exclusive things from Japan. But I must say I bought my amazing magical heattech t-shirts in a very local store at my grandma’s and also in a local gypsy market. Beat it!

10. ¿Cómo era la vida antes de EEUU? How was life before USA?

Me refiero… Estados Unidos ha tenido que marcar un GRAN antes y un después, y no me explico cómo a no ser que dedique días, semanas o meses a estudiarlo…

I mean… United States must have influenced so much Japan that I’d need days, weeks and months to study that phenomena.

Me explico. El idioma japonés tiene MUCHÍIIIISIMOS extranjerismos. Tantos, que crearon un solo alfabeto para ello. Imaginaos. Este alfabeto se denomina katakana. Por otro lado, tienen el alfabeto japonés o hiragana, y el alfabeto chino o kanji, que este último sí que tiene tela y es del que derivan los números que escribí más arriba.

What I’ve noticed. The Japanese language has soooooooo many foreign words. So many that they even created a whole alphabet for them! Imagine that. This alphabet is called katakana. On the other hand, they also have their Japanese alphabet or hiragana and their Chinese one called kanji. The latter is the truly annoying one (cool but so 大変 hard), the one I used for the numbers up there.

Pues, de verdad, hay miles de palabras que provienen del inglés o incluso del portugués (los portugueses fueron los grandes comerciantes con Japón y por eso el pan se dice, ¡afortunadamente!, así, パン /pan/).

I’m not exaggerating, there are thousands of words that come from English or even Portuguese (these were the ones who traded the most with Japan so that’s why bread is called パン /pan/, same as in Portuguese -and Spanish! Lucky us).

Pero, por supuesto, estas palabras están integradas en la pronunciación japonesa, como hacemos los españoles cuando decimos /wifi/ (en lugar de /waifi/), /cruasán/ (en lugar de /kguasán/) o /espiderman/ (en lugar de /spaidermæn/).

However, as we could expect, these words are absolutely integrated in the Japanese pronunciation system, same as we Spanish do with /weefee/ (wifi) or /espeederman/ (Spiderman).

Algunos ejemplos son:

These are some examples:トイレー /toiree/ (toilet), エレベーター /ereveetaa/ (ascensor elevator), ボール /booru/ (pelota ball), スペイン /supein/ (España Spain), レタス /retasu/ (lechuga lettuce), バナナ /banana/ (plátano banana), メロン (meron) (melón melon), ナイフ /naifu/ (cuchillo knife), フォーク /fooku/ (tenedor fork), スープ /suuppu/ (sopa soup), シャワー /shawaa/ (ducha shower)…

Y entonces yo me pregunto: ¿Es que antes no tenían ninguna de estas cosas? ¡Si por ejemplo la sopa es una comida tradicional! ¡Y hasta dicen バイバイ bye bye (adiós) como despedida! Osea, si preguntas cómo se dice «adiós» en japonés, no escucharás JAMÁS el conocido sayonara, sino bye bye.

And so I wonder: Didn’t they have any of these items before USA controlled Japan?! For instance, soup is a traditional Japanese food, so it doesn’t make any sense for me they actually call it ‘soup’. They even say バイバイ bye bye as a farewell! They don’t usually say the worldwide-known ‘sayonara’ but bye bye.

Pues eso, ¿alguien tiene respuesta para alguna pregunta? ¡Estaré encantada de oírla! 🙂

So this is all. Does anyone have any answer for any of these questions? I’d be happy to read it!

PD: La vida en Japón puede resultar desde extremadamente estresante hasta extremadamente cómica. Creo que en mis artículos trato de mostrar la parte cómica, pero siempre desde el más profundo cariño a esta cultura que me ha hecho ver que el mundo no solo es más pequeño y diverso de lo que creía, sino que nosotros debemos creernos y mirarnos el ombligo menos aún de lo que yo pensaba. Todo el tono cómico es siendo consciente de lo que yo he aportado a Japón y sobre todo lo que Japón me ha aportado a mí.

PS: This is all written from my love and admiration towards this different culture. It’s written in a comical style (don’t know if it’s because I’m Andalusian or because life in Japan is like that: you may have a very comical Japanese life or a very stressful one). All I have is respect and thankfulness as we all must learn we are not the center of the world as an individual person or nationality; the world is small and diverse, ready to teach you how to be the best human ever, regardless of your passport (that’s artificial, humanity is natural).

Publicaciones relacionadas / Related posts:

Sobre la Working Holiday en Japón / About Working Holiday in Japan:

- Working Holiday: El seguro médico / My health insurance

- Japan Working Holiday (I): Registration o Cómo empadronarse

- Japan Working Holiday (II): Cómo abrir una cuenta bancaria en Japón / How to open a bank account in Japan being a foreigner

- Japan Working Holiday (III): El permiso de reentrada / The re-entry permit